Over the last 2 years Mrs Jepson Taylor and Mrs Parkin have been actively investigating the impact that instructional coaching has on Sixth Form pupils. Their research found that pupils who participated in a structured coaching programme saw a demonstrable improvement in their self-belief and growth mindset. The techniques and experiences gained from their research is now being shared with other members of staff and students. This research was carried out through the schools Exploring Teacher Programme but has recently been published in the Chartered College of Teachers education journal Impact. You can read the article in full below.

Coaching is viewed as a powerful developmental tool, which enables individuals to make positive life and learning changes (Devine et al., 2013). As part of the Enquiring Teachers programme, a CPD programme that helps to develop a culture of enquiry and professional growth in schools, we were tasked with exploring the impact of teachers working as coaches with pupils. Unlike non-directive coaching, our approach to coaching involves the coach inputting suggestions based on their expertise and experience. Our research taught us that there has been limited research regarding this element of coaching. The largest UK-based research project was conducted in Sandwell from 2003 to 2007 and involved over 18 schools; the conclusion to this project was that ‘coaching can be an effective intervention with a non-adult population in helping students enhance examination results’ (Passmore and Brown, 2009, p. 3). It was felt that working with the Key Stage 5 pupils in our school would be the ideal starting point for school-based research.

Researching the impact

We designed a coaching programme, with accompanying resources and guidance documents, following the GROW coaching model (Abdulla, 2018), whereby sessions are structured to establish the student’s goal, check the reality of what the student has already achieved, think about the options available to them, and gain their commitment (will) to future actions.

Two types of programme were implemented: a general, non-subject, coaching programme with seven interested Year 12 and 13 students, and a subject-specific coaching programme with a class of eight Year 13 English students. An explanation of the purpose of coaching and the expectations of both the coachee and coach was given to all students, and a coaching contract was signed.

Students on the general coaching programme were offered five to six 30-minute weekly individual coaching sessions, held during the spring and early summer half-terms. The majority were face to face, moving to Microsoft Teams during the 2021 COVID-19 lockdown. Students on the subject-specific coaching programme had three coaching sessions over a seven-week period between April mock assessments and May internal examinations. Sessions took place with classroom teachers during timetabled lessons. Feedback from mock assessments was used as a starting basis for goal setting.

The coaching programme

All student sessions followed the same GROW structure, with the focus of the first session being the setting of the final goal, as well as explaining the coaching process. Subsequent sessions included feedback and reflection on performance and progress from the previous session. The final session provided a chance to celebrate achievements and help the student to think about how coaching might assist them in the future.

A wide range of resources was created to allow for consistent delivery and recording of sessions. Student contracts, coaching session record forms and online self-efficacy and feedback questionnaires, along with question banks and resources to use during coaching sessions, were developed to aid delivery.

Measuring impact: Self-efficacy

Measuring the impact and value of this coaching programme was crucial. We wanted to measure the students’ perceptions of goal attainment as well as outcomes such as commitment, resilience, perceived self-efficacy, time management and satisfaction with school life. Bandura (2006) defines self-efficacy as how well one can execute a course of action required to deal with prospective situations. Therefore, within a school, self-efficacy refers to the perception that an individual has about capabilities to perform at an expected level and achieve goals or milestones. We adapted Zimmerman et al.’s (1992) recognised psychometric instrument, the ‘Academic Achievements Scale’, to create a survey, with statements such as ‘I can figure out anything if I try hard enough’ and ‘I can change my basic level of ability considerably’. Responses to these were given on a one-to-six scale of how ‘like me’ the statement was. From this, we could measure how our coachees perceived their ability, their mindsets and how ability might grow with effort.

Coachees were measured prior to their first coaching session and at the end of the programme. A control group of Year 12 students were also measured within the same period. We recorded how close each coachee was to achieving their final goal during every session to allow tracking for coachee, coach and research. We completed 52 coaching sessions – over 34 hours of coaching.

Findings

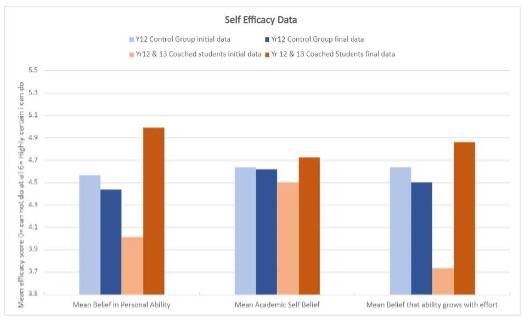

Figure 1: Self-efficacy data

Data was aggregated, as there were no significant differences between the data of both coaching groups. It showed that overall mean self-efficacy scores increased by 13 per cent for the Year 12 and 13 coached students after a programme of coaching sessions (mean Initial 4.08 to mean Final 4.86 out of 6; see Figure 1). Significant changes were seen in students’ ‘belief in their personal ability’ (16 per cent increase) and ‘belief in ability grows with effort’ (19 per cent increase).

When looking at ‘belief in personal ability’, coachees showed demonstrable improvements in knowing how to:

- motivate themselves to do schoolwork (27 per cent increase)

- study to perform well in tests (26 per cent increase)

- plan their schoolwork for the day (23 per cent increase)

- study when there are other interesting things to do (22 per cent increase).

Coachees’ ‘belief that their ability grows with effort’ showed key changes in students’ awareness that:

- They are confident that they will achieve the goals they set for themselves (28 per cent increase)

- If they are struggling to accomplish something difficult, they will focus on progress instead of feeling discouraged (25 per cent increase).

Qualitative feedback

Alongside the data, coaches from both programmes provided rich informal feedback during sessions, recorded by the coach’s in-session notes, and formally via an end-of-programme survey. During analysis, it was found that comments tended to fall into one of three categories: self-reflective (including metacognitive, honest and insightful), skill-building (including academic learning, soft skills and understanding) and affirmations (including of confidence, self-worth and honesty). Themes repeated within these categories – comments along the lines of ‘I’m finding this a process of realisation’, ‘this will go across all my subjects’ and ‘[I am] more confident in myself and my ability’ – were reflective of coachees’ feelings.

Final feedback strongly supported findings and themes from the self-efficacy data, with strong emphasis on the benefit of goal setting and being better able to problem-solve:

… being able to find a logical and easy solution to different problems – able to organise a list of tasks into urgency and importance as well as creating a timetable that isn’t so strict that it’s daunting.

Estelle, Year 12, general programme.

Coachees also appreciated the benefits of the teacher-coach ‘guiding them’, creating personal accountability through the setting of weekly action steps. Feedback included comments such as: ‘being asked “how does this make you feel?” was a reminder that I am working towards my own goals, and I would have to take ownership of my decisions/actions’ (Tianyi, Year 12, general programme, and ‘you have a guide, someone who is not pushing you… It doesn’t feel like a teacher talking’ (Tyler, Year 12, general programme).

Coached students focused on the sense of personalised feedback and support, alongside the impact on their confidence and abilities. They enjoyed opportunities to explore individual learning, with ‘discussing my progress, realising the confidence my teachers have in my ability to succeed’ and ‘feeling I am improving in areas where I have previously struggled’ (Louis, Year 13, subject-specific programme) being indicative comments.

Feedback was incredibly positive, demonstrating that coachees felt the worth of the programme. Remarks during final sessions focused on the positive impact that coaching will have on future learning; one commented, ‘I think goal setting was the most useful thing as it’s something I know I will carry forward’ (Isabella, Year 13, general programme). Students also appreciated the personalised and open coaching relationship: ‘I felt that half-hour really personalised my academic progress’ (Kathleen, Year 13, subject-specific programme) and ‘the mindset of this being non-judgemental means that I can open up’ (Tianyi, Year 12, general programme). The honesty of the coachees, to themselves and to the coaches, is best summed up in one comment: ‘I have never told a teacher before, but I know I am very lazy.’ (Ewan, Year 13, subject-specific programme)

Impact on the coached student

Although to varying degrees, all students learnt how they can develop and how coaching can make a difference, academically and pastorally. For all, the coaching programme demonstrated positive effects on self-belief and development of a growth mindset. The theory, popularised by Carol Dweck, that students’ bel... More. Students learnt problem-solving, goal setting and self-motivation skills; they affirmed this in feedback.

Impact on the teacher as coach

We gained significant personal and professional rewards as teachers working as coaches; we saw students’ positive progression, skill development and confidence improve. Personally, ‘it feels light, a well-done coaching session doesn’t make work for me and is mutually beneficial’ and ‘I always feel quite exhilarated… it is a making a difference moment’. We felt able to achieve positive results in a collaboratively constructive way, rather than dictating actions for students: coachees took more ownership. We noticed our engagement with the students on a level deeper than a normal classroom relationship; this gave us a better understanding of students as individuals. Overall, our experience of being coaches developed our professional skillsets, giving us new tools for teaching, reflection and personal development.

This initial project only allowed us a small insight into the potential positive impacts that coaching could have on students’ wellbeing and learning. Aside from the time-intensive nature of one-to-one coaching, we found no negative takeaways from this project. Within our community, we found limited awareness of student-focused coaching and, moving forward, further research is needed; we are now in the process of looking at how coaching can be effectively implemented.

References

- Abdulla A (2018) Coaching Students in Secondary Schools: Closing the Gap Between Performance and Potential. London: Routledge.

- Bandura A (2006) Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F and Urdan P (eds) Self- Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, Vol. 5. Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing, pp. 307–337.

- Devine M, Meyers R and Houssemand C (2013) How can coaching make a positive impact within educational settings? Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences 93: 1382–1389.

- Passmore J and Brown A (2009) Coaching non-adult students for enhanced examination performance: A longitudinal study. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice 2(1): 54–64.

- Zimmerman BJ, Bandura A and Martinez-Pons M (1992) Self motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal 29(3): 663–676.

Article written by Kate Jepson-Taylor (Business and Economics Teacher) and Sarah Parkin (Head of Scholarship), City of London Freemen’s School